20 Jun Number Authentication: What is the situation in the US? In France?

1 Introduction

Two and a half years ago, the United States passed the TRACED Act[1] , which mandates the authentication of telephone numbers and therefore the use of STIR/Shaken technology for Voice over IP (VoIP). Two years ago, France adopted the Naegelen law, which makes number authentication mandatory.

Since the publication of these laws, US operators have faced multiple deadlines for implementing STIR/Shaken, setting up robocall plans, and registering in the FCC’s robocall database. In France, there has been no communication about authentication outside the circle of operators and the regulator.

The few statistics available on the status of STIR/Shaken adoption in the US show that only a quarter to a third of calls are signed with a STIR/Shaken security certificate and that the number of robocalls has hardly decreased.

Is this a failure of number authentication in the US? Or is it a normal situation because of the many cases in which operators are not yet obliged to authenticate their calls?

What is the state of implementation of authentication in France? What lessons can France draw from the implementation of authentication in the United States? These are the questions to which this document intends to bring a beginning of answer.

2 Principles of the law

The US law is extremely cautious and nuanced and its implementation is progressive. Operators’ obligations were limited to cases where authentication technology was available. These obligations have been phased: first local loop operators with more than 100,000 customers (in June 2021), then virtual operators with less than 100,000 customers (in June 2022), then long-distance operators and non-virtual operators with less than 100,000 customers (in June 2023). The authentication model adopted in the US defines three shades of attestation with which an operator can authenticate a call: A: the call is from one of my customers and he presents a number that he has the right to use; B: the call is from one of my customers but I do not know if he has the right to present that number; C: I receive this call, unsigned, from another operator. Only calls that are not signed when they should be will eventually be terminated by this operator.

The French law is abrupt and without any nuance or progressiveness: a single implementation date (25 July 2023), no exceptions provided for, except for roaming. The operator can only choose between full authentication or call barring. Authentication was introduced at the last minute in the committee at second reading in the National Assembly by the author of the bill. It was rejected by the Senate, which described it as a legislative rider[2], and only reappeared during a haggle in the Joint Committee.

This impulsiveness and ignorance of the details of French law is to be seen in the context of the 2008 constitutional reform, which divides the agenda of the parliamentary assemblies equally between the government and parliament (Article 48 of the French Constitution). A law resulting from a bill introduced by a MP or a Senator will not have been seen by the ministerial departments and will not have been seen by the Council of State. The number of administrators in the assemblies has not been increased in proportion to the time given to parliamentarians to draft their bills.

However, in this case, the alternative was probably between an imperfect law and a project or proposal that would not have been completed during the legislature.

3 Involvement of the legislator and the regulator

The US legislation is very specific about what the regulator (the FCC) must do to implement authentication and report back to Congress.

The French regulator explains to anyone who will listen that French law has not assigned it any such duty or given it any such power.

However, ARCEP is very good at asking the legislator for additional powers when it deems it useful. Last year, it even obtained from Parliament the right to re-introduce a measure that the Council of State had asked it to repeal, as it did not fall within its competence as regulator.

Why then, when it comes to authentication, is ARCEP so restrained in requesting powers that it clearly lacks?

The answer lies in the combination of two factors: on the one hand, after 25 years of managing conflicts of interest between operators and the regulator, no one at the regulator has any experience of the industrial reality of the operator’s job. On the other hand, the influence of a regulator can be undermined by the fact that its decisions are overturned by a higher court. In this respect, ARCEP’s decisions are overturned much less often than those of its Dutch or British counterparts. However, ARCEP’s remarkable track record is perhaps the result of excessive caution in organising industrial ecosystems. The quality of fibre networks, like the management of authentication, is undoubtedly paying the price for this caution.

4 Complexity of the authentication governance model

The basic model for number authentication in the IP world is relatively simple: the request for a phone call (the SIP Invite) is signed by the caller’s operator using a security certificate granted by a certification authority. This certificate consists of a private key, known only to the calling operator, and a public key, used by the called operator to verify that the signature is genuine.

The complexity arises because the law creates a general obligation to authenticate all telephone calls (on origination) and to verify (on termination) that they are all authentic.

The United States has chosen a complex three-tier model for the governance of number authentication:

- a governance authority (STI-GA), which ensures the integrity of the issuance, management, security and use of certificates.

- a Policy Administrator (STI-PA), which is the main operational manager of the system.

- Certification Authorities (STI-CA), which issue certificates to operators that have been validated.

The United States has chosen to allow multiple certification authorities. As a result, a transit or terminating operator wishing to verify the authenticity of a call must match the request from its verification service against the public key issued by the certification authority chosen by the originating operator of the call it receives. This involves automating the certificate issuance and verification process, according to the ACME protocol (RFC 8555).

In France, the choice of a single certification authority model (APNF) simplifies the governance problem and allows the technical architecture to be simplified. As a result, the technical model chosen in France does not include the ACME protocol. This simplification is justified as long as authentication is only provided for national calls. If authentication were to become a Europe-wide obligation, it is likely that the ACME protocol would become necessary.

5 Completeness of the authentication model

5.1 General case

The core model of authentication consists of four main phases:

- KYC (Know your customer): this refers to the steps that the operator must take to ensure the identity of its customer and the customer’s right to present a given telephone number,

- Signature: this is the sending in the SIP Invite request of a field, named Identity, and signed with the private key of the certificate granted by the certification authority,

- Verification: this is the verification by the operator receiving the call that the signature has been made with a valid certificate,

- Interrupting fraudulent or unauthenticated calls.

This central model is to be completed by two control loops:

- The system’s operating statistics,

- Traceback, or tracing back to the originating customer of unauthenticated or fraudulent calls.

KYC is straightforward in the case of face-to-face sales and of use by the customer only of numbers allocated to them. KYC becomes complex in the case of online ordering, of resale of subscriptions and/or numbers, or of the legitimate presentation of a third party’s number. On the one hand, France and the US face the same challenges in this respect: documents uploaded in an online sale must be verified by a human being, as must the right to present a third party’s number. On the other hand, under US law, local loop operators do not have the right to object to the resale of their services, whereas the French numbering plan progressively restricts the right to make numbers available to anyone else than the end user. In this respect, the task of identifying the true customer will be easier in France.

Signature and verification work in the same way in France and the United States.

The obligation to terminate unauthenticated calls is much more limited in the US than in France. In the US, it only covers calls from operators who have not registered with the FCC’s RobocallMitigation Database. In France, according to the law, any unauthenticated call (as defined by the A attestation) must be disconnected. It is difficult to see how such a requirement could be met in the foreseeable future.

With regard to feedback loops, the US has developed several distinct tools:

- Traceback is provided by an industry consortium (USTelecom – Industry Traceback Group) selected by the FCC,

- Reporting is done through the FCC portals dedicated either to consumers or to private legal entities.

In France, the APNF plans to set up not only a Database of Operators’ Certificates (as required by its role as certification authority), but also a Database of Signals and Measurements which will centralise the traces of calls deserving to be terminated and of calls actually terminated, as well as the incidents and reports issued by operators. It is possible that the centrality of the French model will ultimately provide better visibility of the operation of authentication than the decentralisation adopted by the US.

5.2 Special cases: legacy technologies

The US law takes into account the fact that legacy technologies (e.g. PSTN, or voice over 2G/3G mobile networks) either do not offer a solution for authentication or provide solutions that would be prohibitively expensive to implement. As a result, telephony systems that do not use the SIP protocol are exempt from implementing STIR/Shaken in the US.

In France, the law makes no such exception. Industry reality being what it is, non-SIP networks will not provide authentication and will therefore contravene the law.

5.3 Special cases: standards that are too young

Many common but complex uses (call transfers and forwarding, presentation of third-party numbers by companies, etc.) require, in order to be authenticated, standards adopted very recently[3] and the implementation of which, although fully envisaged in the long term, is not compatible with the deadline of the French law in 2023. The same applies to ensuring that emergency calls can be completed even without authentication. In the United States, the law provides and the regulator’s decisions ensure that nothing impossible is required of operators.

6 Schedule of requirements

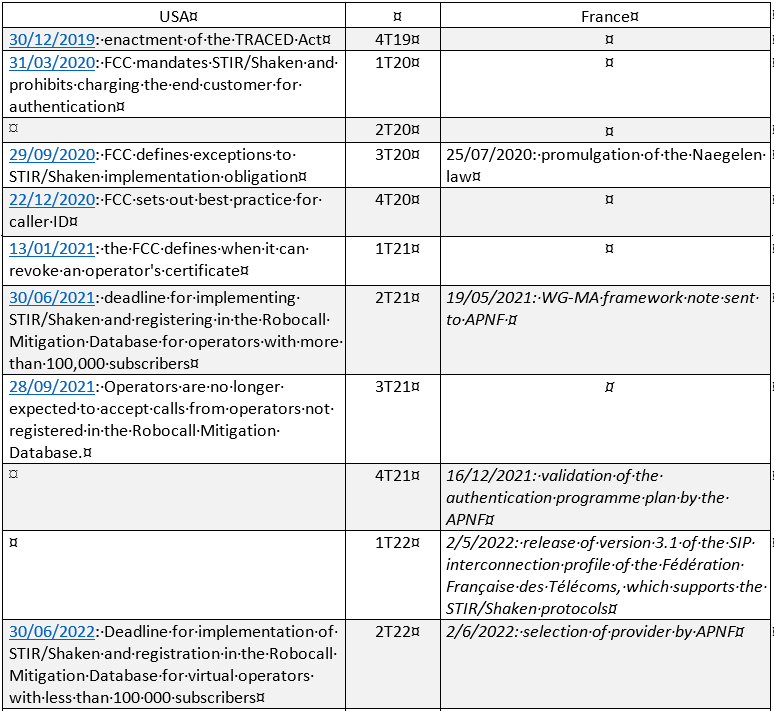

Table 1 below shows the main deadlines for number authentication in France and in the United States. The multiplication of milestones set by Congress and the FCC offers a sharp contrast with the official silence of the French legislator and regulator regarding the phasing of objectives.

However, the French operators have made progress, first by producing a framework note in May 2021, within the GT-MA, a working group hosted by ARCEP, and then in the form of work undertaken in their joint professional bodies:

- In May 2022, the Fédération Française des Télécoms published a new version of its national SIP interconnection profile. This new version includes in the SIP Invite request the Identity field, which contains the information required by the STIR/Shaken protocols.

- The APNF[4] adopted a programme plan for the number authentication mechanism in December 2021, and in May 2022 published the specifications for the operator certificate base. In June 2022, the APNF selected its technical provider to deliver the system in the first quarter of 2023, in order for operators to be integrated into the system from the second quarter of 2023 on.

Table 1 – Schedule of number authentication requirements

In the US, the law and the regulator are organising a very gradual increase in requirements. Operators with less than 100,000 subscribers are not required to implement STIR/Shaken on their SIP networks until 30 June 2022, if they are non-facilities-based, and by 30 June 2023 if they operate their own facilities, and intermediate providersare not required to do so until 30 June 2023.

In France, the law states an absolute requirement for all operators to authenticate on the same day (25 July 2023) but the industrial reality will be much more progressive:

- The operators’ plan only provides for authentication of SIP calls (about 20% of calls).

- The integration of the SIP operators with the APNF MAN system will take place throughout 2023.

- Call transfers and call forwarding will not be authenticated in 2023; neither will the protection of emergency calls against the risk of interruption for lack of authentication.

Under these conditions, it is unthinkable to stop unauthenticated calls for several years.

7 Pace of compliance by operators

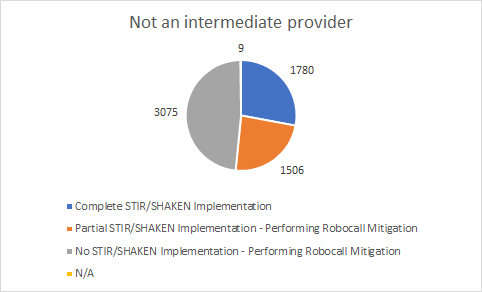

Is the US rollout of authentication proceeding normally given the temporary exceptions granted? To answer this question, let’s compare three data sources:

- The proportion of US operators who report having implemented STIR/Shaken (fully, partially, not at all) or who were exempt,

- The proportion of calls seen by two players (Transnexus and Next Caller) signed STR/Shaken or not.

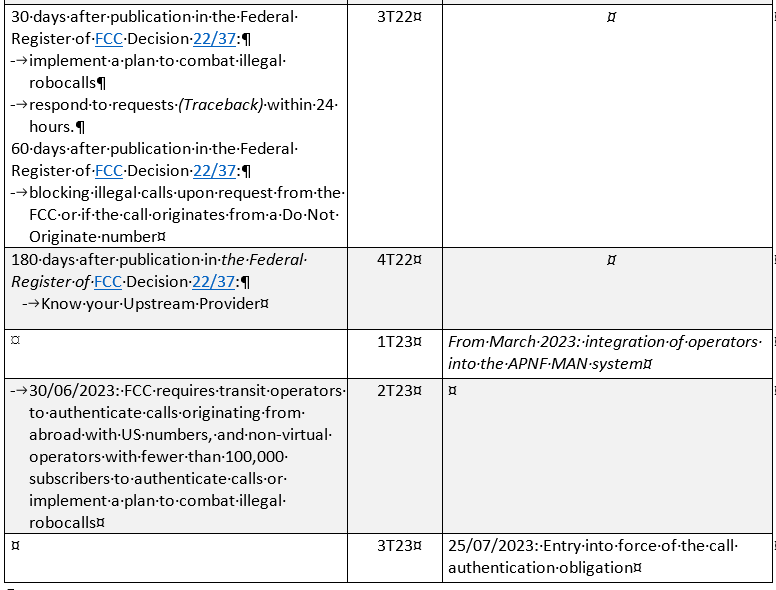

The FCC’s Robocall Mitigation Database, consulted on 14 June 2022, includes 7442 operators. As these are operating companies and not groups, the big names in American telecoms (AT&T, Verizon, etc.) are listed under each of their local or specialised operating subsidiaries. The database distinguishes 6370 originating and terminating voice service providers (see Figure 1), who assign telephone numbers to customers. These operators had to have implemented STIR/Shaken by 30 June 2021 if they had more than 100,000 subscribers, by 30 June 2022 for virtual operators with less than 100,000 subscribers and by 30 June 2023 for the others. The 1072 intermediate providers, on the other hand, will only be obliged to do so from 30 June 2023. Of the 6370 orignating and terminating voice service providers, 24% report having fully implemented STIR/Shaken, 21% have partially implemented it and 48% have not.

Figure 1 – Number of originating and terminating voice service providers registered in the FCC Robocall Mitigation Database as of 14 June 2002

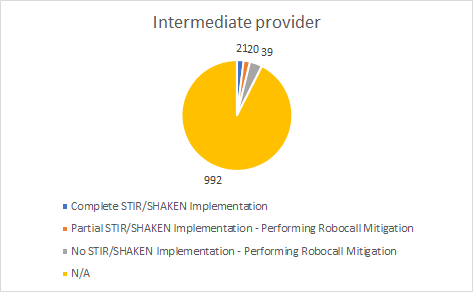

The intermediate providers (see Figure 2) had not, with a handful of exceptions, implemented STIR/Shaken by 14 June 2022, which is normal, as they will only be obliged to do so by 30 June 2023.

Figure 2 – Number of intermediate providers registered in the FCC Robocall Mitigation Database as of 14 June 2002

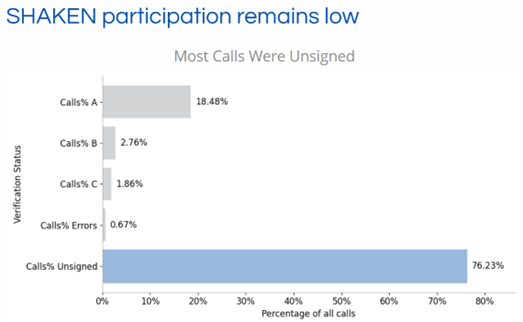

Transnexus, a company offering software to manage and protect telecom networks, has been publishing monthly STIR/Shaken statistics since April 2021. These figures are collected from over 100 voice service providers using its STIR/Shaken and robocall solutions. The data describes the calls they have received from 283 other voice service providers who have made calls, including some automated calls, signed with STIR/Shaken. As shown in Figure 3 below, as of May 2022, 76% of calls seen by Transnexus systems were not STIR/Shaken signed.

Figure 3 – Use of STIR/Shaken as seen by Transnexus in May 2022

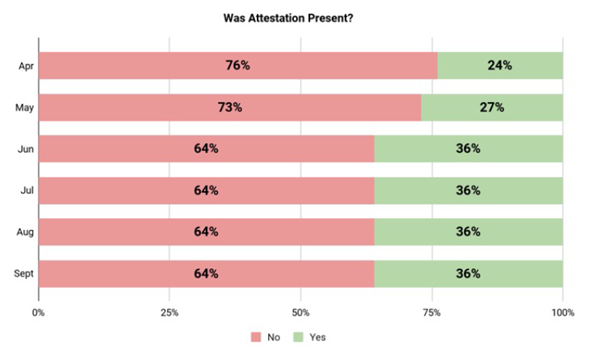

From April 2021 to September 2021, Next Caller, a Pindrop Group company, examined (see Figure 4) the SIP header information of approximately 109.5 million telephone calls from over 500 originating carriers, including the major voice service providers. Interestingly, as shown in the figure below, one of Next Caller’s first observations was that, despite the obligations imposed by the FCC, a large majority (64% to 76%) of these calls did not include any STIR/Shaken certification from an operator.

Figure 4 – Next Caller observations from April to September 2021 on the presence of STIR/Shaken signatures in calls whose details were recorded in their systems

The percentage of US originating and terminating operators that have deployed STIR/Shaken (24% fully and 21% partially) is consistent with the percentage of STIR/Shaken signed calls reported by Transnexus (24% in May 2022) or by Next Caller (36% in September 2021)

At the end of June 2023 the grace period for small operators expires. A large number of small business operators will need to have deployed STIR/Shaken by this date. What will be the resulting increase in the percentage of STIR/Shaken signed calls? We will know in early August 2023.

In France, the prohibition on accepting a call with a French number on an incoming international interconnection circuit dates back to an ARCEP decision that came into force in August 2019.

As far as STIR/Shaken is concerned, the compliance of operators required for July 2023 will be subject to two bottlenecks: 1. The capacity of operators to implement call signature and verification, 2. the capacity of the service provider chosen by the APNF to make operators undergo the integration tests for the number authentication mechanism. The 300 or so French telephone operators will not pass these tests in three or four months, from April to July 2023. The integration tests are expected to be staggered at least until the end of 2023.

Once this integration is done, what rate of adoption of STIR/Shaken should we see in France?

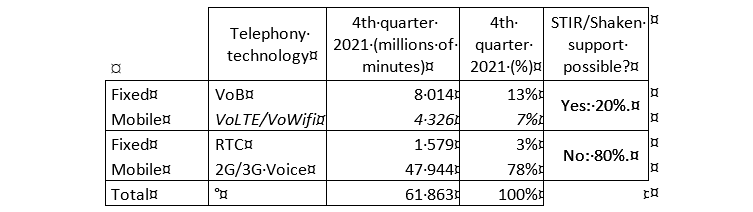

The ARCEP data from the Observatoire des Marchés give us information on the rate of use of the various telephony technologies: for fixed networks, PSTN and VoB (Voiceover Broadband) are distinguished. For mobile networks, total traffic is given, as well as VoWifi[5] traffic. Only the details of VoLTE[6] traffic are missing. If we estimate it to be equal to VoWifi traffic, we see that in the conditions of the last quarter of 2021, 20% of phone calls (counted in minutes) were in SIP, and therefore likely to support STIR/Shaken protocols. By the beginning of 2024, this percentage will probably have risen slightly, but, as in the US, STIR/Shaken authentication will still only concern a minority of calls in France.

Table 2 – Estimated share of telephone calls likely to support STIR/Shaken protocols in France in 4th quarter 2021 (Source: ARCEP)

8 Conclusion

Number authentication is an indispensable technology for law enforcement in the domain of telephony. However, its implementation requires a long-term effort, probably until the end of the decade. The French law has had the merit of launching the effort, but it would benefit from recognising this fact. Otherwise, operators who have done nothing to comply will be able to point to those who have made partial implementations (i.e. on their SIP networks, but not on their other networks) as not complying with the law either. The effort required to go beyond the authentication foundation built by operators for 2023 will no longer have the character of a precise deadline, as the legal date of the obligation will have been largely exceeded, and for good reasons.

Does the non-support of STIR/Shaken by TDM technologies (PSTN, voice over 2G/3G) cause an irreparable delay in the fight against illegal calls? This is not certain, because TDM technologies impose a limited, rigid, and predefined number of simultaneous calls. For this reason, most of the senders of illegal calls use SIP, a much more flexible technology, both in terms of simultaneous calls and simultaneous call attempts. Full authentication of SIP calls should therefore significantly reduce the number of illegal calls.

However, as long as the interruption of unsigned STIR/Shaken calls is not possible, the traceback of illegal calls to the sender will be indispensable, although not automated. France has no specific system for this. Automated administrative (and not only judicial) disclosure of communication data by all operators, as is the case in Germany and the Netherlands, could help in this respect.

Finally, both in the United States and in France, the highly fragmented nature of the available statistics raises questions. The FCC collects detailed interstate and intrastate revenues from US operators for the financing of universal service, ARCEP publishes the Observatoire des Marchés, but neither of these two regulators apparently considers publishing call-by-call statistics on the use of STIR/Shaken. There is a questionable lack of a dashboard.

___________________

[1] The ”Pallone-Thune Telephone Robocall Abuse Criminal Enforcement and Deterrence Act” or the ”Pallone-Thune TRACED Act

[2] A legislative rider is a measure introduced in a bill that has no relationship with the purpose of the bill.

[3] For call transfer and call forwarding, see RFC 8946. For presentation of third party numbers, see RFC 9060. For emergency calls, see RFC 9027.

[4] APNF: the Association des Plateformes de Normalisation des Flux interopérateurs (APNF) is an association open to all electronic communications operators offering the telephone service to the public using numbering resources belonging to the French telephone numbering plan. The APNF provides its members with services relating to fixed number portability, value-added services, emergency call location and soon number authentication in France.

[5] VoWifi: voice over Wifi is a technology that makes it possible to use the fixed IP network and its Wifi termination in place of the 4G or 5G cellular network to call from a mobile terminal. VoWifi uses the SIP protocol and therefore lends itself to number authentication using the STIR/Shaken protocols.

[6] VoLTE: Voice over LTE refers to telephony in IP mode on mobile networks. It is only available on 4th and 5th generation networks. VoLTE supports STIR/Shaken number authentication protocols, unlike circuit mode voice of 2nd and 3rd generation mobile telephony.